What is Swimmer’s Itch and How Can I Help Prevent It?

Click Button Above to Review Data

Click Button Above to Review Data

Click Button Above to Review Data

Click Button Above to Review Data

Information below are excerpts from the Cleveland Clinic Swimmer’s Itch Webpage

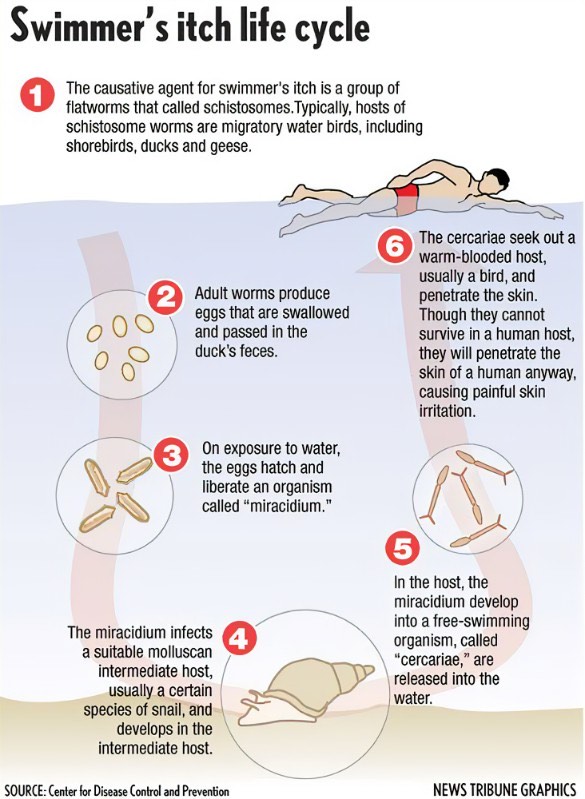

Swimmer’s Itch (cercarial dermatitis) is a skin rash that you can get if you’ve have swum in fresh or salt water that is infested with a certain parasite. It is an allergic reaction, so it is not contagious and will eventually go away on its own. The main symptoms are a rash with reddish pimples and itching or burning. There is no treatment for it, but over-the-counter treatments can relieve the itching.

Swimmer’s itch (cercarial dermatitis) is a temporary, non-contagious itchy rash that appears on your skin and is caused by a certain parasite found in fresh water (lake or pond water) or salt water (ocean water). If you swim in water that’s infested with the parasite, it can burrow (dig) into your skin. Your body has an allergic reaction to it, causing a rash. The parasites cannot survive in human skin, so they die shortly after burrowing into your skin. The rash usually gets better after a few days, but it can last for up to two weeks.

The parasite larvae that cause swimmer’s itch are known as cercariae. The parasites that cause swimmer’s itch originate from infected birds that live near water, such as ducks, geese and gulls, and mammals like beavers, muskrats and raccoons. The parasites lay eggs in the infected animal’s blood and then the eggs are passed through the infected animal’s poop.

If those eggs reach water, they hatch and release tiny, microscopic larvae. These larvae swim around the water looking for a certain species of snail, and if they come into contact with the snail, the larvae will multiply and further develop. Infected snails then release a different kind of larvae known as cercariae, which is why swimmer’s itch is called cercarial dermatitis. This kind of larvae then swims to the surface of the water looking for certain birds or mammals to continue the cycle.

Even though the larvae cannot survive in a human’s body, they can burrow into a swimmer’s skin and trigger an allergic reaction that causes an itchy rash, known as swimmer’s itch. The larvae soon die after they burrow into a person’s skin, but the itching and rash from the allergic reaction can last for several days. Swimmer’s itch (cercarial dermatitis) looks like a rash with reddish bumps or pimples. It may also cause small blisters on the skin and itch or burn. Swimmer’s itch can only appear on skin that has had contact with infested water.

Swimmer’s itch (cercarial dermatitis) is a common condition. It happens around the world and is more frequent in summer months when people are more likely to swim. Getting swimmer’s itch from fresh water, like lakes and ponds, is more common than getting it from salt water (the ocean). Swimmer’s itch can happen to anyone who swims in water that is infested with the parasites that cause swimmer’s itch. Young children are more likely to get swimmer’s itch because they are more likely to wade and play in shallow water where the parasites are more likely to be found. You can get swimmer’s itch on your body anywhere that the parasites from the infested water have come into contact. The legs are a common area to get swimmer’s itch since they are the part of your body that is most likely to be in the water, whether you are walking, wading or swimming in it.

How is swimmer’s itch (cercarial dermatitis) treated?

There is no prescribed or formal treatment for swimmer’s itch. It usually goes away within a week. To get relief from symptoms and itching, you can try the following things at home:

- Apply a corticosteroid cream to the affected area.

- Apply a cool compress to the affected area.

- Use an anti-itch lotion (like calamine) on the affected area.

- Soak in a colloidal oatmeal bath or an Epsom salts bath.

- Make a baking soda paste with baking soda and water and apply it to the affected area.

How do I get rid of swimmer’s itch (cercarial dermatitis)?

Since swimmer’s itch is the result of an allergic reaction, there is nothing you can do to get rid of the rash itself. Your body will eventually heal itself, and the rash will fade away. You can try to relieve the itchiness by using certain at-home remedies like soaking in a colloidal oatmeal bath or using a corticosteroid cream. You can also prevent the rash from getting worse by not scratching it too much or too hard. A lot of scratching can cause an infection.

How long does swimmer’s itch (cercarial dermatitis) last?

Swimmer’s itch usually goes away on its own within a week, but it could take longer, especially if you have swam in the infested water consecutive times or days. Contact your healthcare provider if your rash lasts longer than two weeks or if there is pus coming out of your blisters.

What can I do to reduce my risk of getting swimmer’s itch (cercarial dermatitis)?

There are a few things you can do to reduce your risk of getting swimmer’s itch, including:

- Rinse off with clean water after swimming: Rinse your body with clean water right after you’re done swimming. Be sure to dry your skin well with a clean towel.

- Choose where you swim carefully: Look for signs near the swimming site that could warn you of possible swimmer’s itch contamination and try not to swim in places where swimmer’s itch is a known or common problem.

- Do not feed birds or animals near where you are swimming: Birds and mammals that live near fresh water or salt water can carry the parasite that causes swimmer’s itch. You don’t want to make them come closer to areas where people are swimming, because they could spread the parasites.

- Do not swim or wade in or near marshy areas: Snails are more likely to be found in marshy areas, and they can be infected with the parasite that causes swimmer’s itch.

- If possible, try not to swim or wade in shallow water or by the shoreline: The parasites that cause swimmer’s itch are more likely to be found in shallow water or by the shoreline. If you’re a strong swimmer, consider swimming in deeper water to try to avoid the parasites.

- Apply waterproof sunscreen. This has been reported to protect the skin from the parasite that causes swimmer’s itch. (Last bullet from Mayo Clinic link)

See more information and advice on preventing swimmer’s itch contact the Minnesota Department of Health, Acute Disease Epidemiology at 612-676-5414

or Contact Your Doctor

Swimmer’s Itch Red Spot Rash Examples

——————————-

DNR Fish Stocking Information as of March 15, 2022

Summary

- Battle Lakes annual DNR stocking plan target is now 1248 lbs. of fingerings annually. This started last year.

- Actual stocking in 2021 was 2060 lbs., which were all were approximately 2-year-old quite large fish!

- Actual 2021 muskie stocking was 500 fish

- Targeted 2022 walleye stocking is 1248 lbs. of fingerings, hopefully this can be exceeded again as it was last year. This is dependent on the pond quota achievement.

- Targeted 2022 muskie stocking is 2500 fish

====================================

Please Place Fire Pits at Least 50 Feet from the Lake!

Zebra Mussels’ Best Friend: Wake Board Boats a University of Minnesota Study Finds!

Click HERE to See More Information

*******************

Is there a DNR Form I need to Have to Transport Watercraft from and AIS Infested Lake such as West Battle Lake?

Yes there is! Please Click HERE to view, print or download the DNR Form

Do You Care for an Aquarium or Water Garden Pond?

If So, Read On! . . .

The DNR is conducting a survey of aquarium and water garden pond owners in the state. We need your advice, to help us prevent the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive plants and animals to Minnesota’s waters. Invasive species are non-native species that present risks to Minnesota’s fish, wildlife, plants, water quality, recreation and human health.

Many invasive species have been introduced through global shipping, but hobbies that involve live organisms, such as aquariums and ponds, have also led to the introduction and spread of some invasive species. Some examples of invasive species that have unfortunately been found in the wild in the Great Lakes region through these pathways include goldfish, red-eared sliders, flowering rush and Brazilian waterweed.

In 2019, the DNR met with representatives of the pond and aquarium industry and hobby groups to discuss how to prevent the spread of invasive species. All participants agreed that they had a role to play and felt that more information was needed to determine how best to proceed. In the spirit of cooperation and to improve our programs and outreach, the DNR seeks to better understand aquarium and pond owners’ motivations, concerns and practices. We want to know how we can improve our educational materials, the best ways to communicate with hobbyists, where hobbyists like to get their aquarium plants and animals, and what hobbyists do with animals and plants they can no longer care for.

If you are an aquarist or water gardener, please help us to protect our natural resources and provide better service to aquarium and pond owners by taking the online survey.

Want more information? Check out these webpages:

Trade pathways for invasive species introductions

Hobbyists: Responsible buyers

Businesses: Pet and Aquarium and Horticulture

===================================

You Can Find the Updated DNR List of Infested Waters Online

What’s On the List?

The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) regularly updates the state infested waters list, which includes Minnesota lakes and rivers containing certain aquatic invasive species.

If you harvest bait, fish commercially, or divert or take water from lakes or rivers on this list, you may need to follow special regulations.

- The most complete and up-to-date list of infested waters is an Excel spreadsheet available on the DNR website.

- Using the Excel spreadsheet, you can sort, search or filter the list by water body name, county, species, or year. If you have questions about what the information means, see the tab called “Column descriptions”.

Questions about the infested waters list?

Contact Kelly Pennington, Aquatic Invasive Species Prevention Consultant

Questions for your local aquatic invasive species staff? Contact us

Helpful Information on the Responsibility of Owners and Their Lake Equipment

Is there a DNR Form I need to Have to Transport Watercraft from and AIS Infested Lake such as West Battle Lake?

Yes there is! Please Click HERE to view, print or download the DNR Form

——————————–

More Key Questions with Answers . . .

Hiring Businesses to Install or Remove Water-related Equipment

If you hire a business to install or remove your boat, dock, or lift, or other water-related equipment, make sure they have completed AIS training and are on the DNR’s list of Permitted Service Providers. Lake service providers that have completed DNR training and obtained their service provider permit will have a permit sticker in the lower driver’s-side corner of their vehicle’s windshield. They have attended training on AIS laws and many have experience identifying and removing invasive species.

Moving Docks, Lifts, and Equipment to Another Waterbody

If you plan to move a dock, lift or other water equipment from one lake or river to another, all visible zebra mussels, faucet snails, and aquatic plants must be removed whether they are dead or alive. You may not transport equipment with prohibited invasive species or aquatic plants attached. The equipment must be out of the water for 21 days before it can be placed in another waterbody.

Storing Lifts and Docks for Winter

You may remove water-related equipment from a water body – even if it has zebra mussels or other prohibited invasive species attached – and place it on the adjacent shoreline property without a permit.

However, if you want to transport a dock or lift to another location for storage or repair, you may need a permit to authorize transport of prohibited invasive species and aquatic plants.

Transporting Watercraft for Storage

You may not transport any watercraft with zebra mussels, faucet snails, or other prohibited invasive species or aquatic plants attached away from a water access or other shoreland property, even if you intend to put it in storage for the winter.

If you need to transport your watercraft at the end of the season, you may need a permit to authorize transport of prohibited invasive species and aquatic plants.

Transporting Aquatic Plants for Disposal

You may not transport aquatic plants from a shoreland property to a disposal location without a permit. Shoreland owners interested in transporting aquatic plants – including aquatic plants with prohibited invasive species attached – to a disposal location must complete and sign a permit to authorize transport of aquatic plants and attached prohibited invasive species.

Click URL Link Below to View Additional Answers to FAQ

http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/lakes/faqs.html

Do I Need a DNR Permit to Remove the Cattails Along my Lakeshore?

The control or removal of emergent aquatic vegetation, such as cattails, bulrushes or wild rice, does require a DNR aquatic plant management permit). The DNR Section of Fisheries regulates the control or removal of aquatic vegetation by physical or chemical means. Permits can be applied for through the DNR Regional Fisheries Office serving the area where your shoreline property is located. They may be contacted at (651) 259-5100 for more information.

What are “Environmental” Lakes? Are they wild? Are there Restrictions on Motors or Hunting and Fishing?

The term “environmental lake” most likely is taken from the Natural Environment Lake classification found in Minnesota’s Shoreland Management Program. Many people mistakenly infer that the Natural Environment classification on many of Minnesota’s smaller, shallow lakes means they are wild lakes with limits on motors, hunting or fishing. To a degree, this is true in that Natural Environment is the strictest of the three lake classifications. However, the classification is used to determine lot size, setbacks and, to a certain degree, land uses on the adjacent land. The classification has nothing to do with surface water use of boats or motors, hunting and fishing or fish management. These are governed by other regulations. As the larger, deeper lakes that are more suitable for recreational or general development (the other two lake classifications) become developed, there is growing pressure to develop the smaller, more sensitive natural environment basins. Hence there is no guarantee that the wilderness character that some of these lakes now have will be preserved. It is a growing concern of many local governments, outdoors recreation groups and the DNR that such lakes may require more protection than currently provided in the rules.

The shoreland management rules were established in the early 1970’s and are intended to help govern the orderly development of land adjacent to Minnesota’s many lakes and rivers. The way it works is that DNR established statewide standards and lake/river classifications that local governmental units (counties and municipalities) were then required to incorporate into their land use controls (planning and zoning ordinances). To learn more, click on the Guide for Buying and Managing Shoreland. There you can find information on the lake classification system along with a more complete explanation of the shoreland management program.

How are Lakes Defined in Minnesota?

A lake is not defined by size or depth as some may suggest. A lake may be defined as an enclosed basin filled or partly filled with water. A lake may have an inlet and/or an outlet stream, or it may be completely enclosed (landlocked). Generally, a lake is an area of open, relatively deep water that is large enough to produce a wave-swept shore. For regulatory purposes, Minnesota has grouped its waters into two categories: public waters and public water wetlands. This makes it easier to determine whether a DNR public waters work permit (available under DNR Waters Forms) is required before changes can be made to the course, current, or cross section of these waters.

The state has an interest in protecting not only the amount of water contained in these lakes, wetlands and streams but also the container that confines these waters (i.e., lakes, wetlands, and streams). The obvious reason for these conservation measures is that these waters provide a vital habitat for fish and wildlife, as well as a place for people to fish, hunt, trap, boat, and swim. However, the most important benefits provided by these waters are less obvious:

- Substantial amounts of water are stored in these areas, and it can seep into the ground to recharge ground water aquifers.

- Lakes, wetlands, and streams can store excess water in times of flooding and provide an important reserve of surface water during times of drought. These areas are nature’s water treatment systems. They provide an ideal environment for aquatic vegetation and animal organisms to purify the water we have contaminated with suspended soil (erosion), nutrients (from fertilizers and animal wastes), and other pollutants.

How Do I Go About Naming a Lake?

Naming lakes, rivers, streams or other water bodies (natural geographic features) in Minnesota is guided by the statutory process found in Minnesota Statute 83A.04 – 83A.07. The process requires 15 or more registered voters to petition the county board of commissioners in the county where the feature is located for a public hearing concerning a proposed name. If the public hearing is successful, the county board would adopt a resolution in support of the proposed name (or other name if favored by the board as a result of testimony at the hearing) and forward it to the state commissioner of natural resources. The name proposed in the resolution MUST be approved by the commissioner of natural resources to become the official name of the feature in Minnesota. Approved names are subsequently submitted to the United States Board on Geographic Names for federal approval and use.

The process to change a name is the same. However, a name that has existed for 40 years or more may not be changed. Also, the commissioner of natural resources will not approve a name that commemorates, or may be construed to commemorate, living persons. For additional information, please contact Peter.Boulay@state.mn.us; telephone (651) 296-4214.

What is a “Spring-fed” Lake?

To varying degrees many, if not most lakes receive some water from ground water sources or are “spring fed.” When swimming, one might notice colder, localized areas or areas of the lake might remain open along the shoreline during winter. Both are likely due to ground water flowing into the lake. Lakes also lose water to ground water sources. Most lakes have both; some ground water flows into the lake and some lake water flows into the ground water system or aquifer. Variations in precipitation patterns can cause the amount in or out to change significantly. Generally, complex hydrologic computer models including information such as watershed, geology, precipitation, lake level, and ground water level data are used to estimate how much is flowing in or out of the lake.

What is a Meandered Lake?

A meandered lake is a body of water, except streams, located within the meander lines shown on plats made by the United States General Land Office (Federal Bureau of Land Management). A meander line is a series of courses and distances to delineate the area of a body of water. It is not a boundary line, nor does it convey land ownership information.

What is the Definition of Public Waters?

(See complete legal definition under Public Waters Work Permits Program.) Public waters are all water basins and watercourses that meet the criteria set forth in Minnesota Statutes, Section 103G.005, Subdivision 15 and are designated on the DNR’s Public Waters Inventory Maps.

What is the Definition of Ordinary High-water Level (OHWL) and Why is it Important?

The ordinary high-water level (OHWL) is a reference point that defines the DNR’s regulatory authority over development projects that are proposed to alter the course, current, or cross section of public waters and public waters wetlands. For lakes and wetlands, the OHW is the highest water level that has been maintained for a sufficient period of time to leave evidence upon the landscape. The OHWL is commonly that point where the natural vegetation changes from predominately aquatic to predominantly terrestrial. For watercourses, the OHWL is the elevation of the top of the bank of the channel. For reservoirs and flowages, the OHWL is the operating elevation of the normal summer pool. The OHWL is also used by local units of government as a reference point from which to determine structure setbacks from water bodies and watercourses. See also legal definition under Hydrographics Program.

Also see technical paper (TP #11) “Guidelines for Ordinary High-Water Level (OHWL) Determinations”. This paper reflects current terminology as well as the DNR Area Hydrologists’ addresses and phone numbers.

Why is the Water Level on My Lake so High or so Low? What is the DNR Going to Do About It?

The DNR does not control the water level elevation of lakes. In general, the water level of a lake is entirely dependent upon the amount of snowfall and precipitation that an area receives, how much of the resultant moisture is contributed by runoff into the lake, how much water is recharged to or discharged from the lake through ground water and how much water evaporates from the lake. In some instances, the water level is controlled by illegal human activity or beaver activity. See also the DNR Lake Level Minnesota Program, for information about lake gauge measurements and lake levels.

What is Meant by “Lake Turnover”? How and Why Do Lakes Do This in Autumn and Spring?

- The key to this question is how water density varies with water temperature. Water is most dense (heaviest) at 39º F (4º C) and as temperature increases or decreases from 39º F, it becomes increasingly less dense (lighter). In summer and winter, lakes are maintained by climate in what is called a stratified condition. Less dense water is at the surface and more dense water is near the bottom.

- During late summer and autumn, air temperatures cool the surface water causing its density to increase. The heavier water sinks, forcing the lighter, less dense water to the surface. This continues until the water temperature at all depths reaches approximately 39º F. Because there is very little difference in density at this stage, the waters are easily mixed by the wind. The sinking action and mixing of the water by the wind results in the exchange of surface and bottom waters which is called “turnover.”

- During spring, the process reverses itself. This time ice melts, and surface waters warm and sink until the water temperature at all depths reaches approximately 39º F. The sinking combined with wind mixing causes spring “turnover.”

- This describes the general principle; however, other factors (including climate and lake depth variations) can cause certain lakes to act differently. A more detailed description of the physical characteristics of lakes, including temporal and density interactions, can be found at the Water on the Web site, sponsored by the University of Minnesota – Duluth and funded by the National Science Foundation.

What Can I Do to Prevent Erosion?

Two general methods are available to prevent your lakeshore from eroding: hard armoring and soft armoring. The most common hard-armor technique is riprap, which consists of placing large rocks in the water and up the slope of the eroding shoreline. Riprap is commonly used to control erosion along streambanks and lakeshores where vegetation is not sufficient to prevent erosion caused by high water or wave action. It is expensive to install and is often installed incorrectly. If installed properly, however, riprap normally provides good protection from the impact of waves and ice. Some believe that riprap is overused and unsightly and that Minnesota lakes have lost much of their natural shoreline to riprap.

In contrast to hard-armor techniques, soft-armor methods use organic and inorganic materials combined with plants to create a living barrier of protection. Bioengineering, a soft-armor method, provides erosion control through the use of live vegetation. Bioengineering can be used in addition to or in place of hard armor such as rock riprap. It creates a more natural, environmentally friendly shoreline that includes additional benefits to erosion control, such as habitat enhancement. An excellent source of information on these methods is the DNR publication “Lakescaping For Wildlife and Water Quality” available from the Minnesota’s Bookstore. A DNR public waters work permit (application available under DNR Waters Forms) may be required for both soft and hard armoring methods.

What is a Lake Improvement District (LID)?

A Lake Improvement District (LID) is special-purpose district formed around a lake in accordance with Minnesota Statutes, sections 103B.501-103B.581. A lake improvement district is a local unit of government established by resolution of appropriate county boards and/or city governing bodies, or by the commissioner, for the implementation of defined lake management projects and for the assessment of the costs thereof.

Where Can I Purchase a Lake Map? Where Can I Obtain a Printout with Information on What Kind of Fish are in My Lake (i.e., Lake Survey Maps)?

DNR lake maps can be purchased at Minnesota’s Bookstore. Printouts of lake survey reports, depth maps, and fish consumption advisories are available from the DNR Lakefinder.

What are the DNR Waters Permitting Requirements for Lakefront Property?

See the water permits page to learn when you need a permit.

Who Owns the Lakebed?

Read the article Pardon Me Myth! Who Owns the Lakebed? by Dave Milles

More DNR Info . . .

Click URL Links Below to View